The dataset used and some graphs I share throughout the report are available to the public here. Please play around and find where your favorite driver is relative to average finish (x-axis) and performance versus teammates (y-axis)!

Since I began writing about the junior levels of American open-wheel racing in 2022, my interest has always been with what exactly makes a good prospect.

Racing lacks quantifiable, objective metrics like American football’s 40-yard dash or measuring velocity and spin rate amongst baseball pitchers to measure young talent.

This is because even in spec series where most parts are controlled, no two cars in motorsports are equal.

As is the case at this level, budgets determine which opportunities are available for drivers and who can or can not advance. With it costing hundreds of thousands of dollars to run a single season in the USF Pro Championships and above a million to run in Indy NXT, there are clear correlations between what a driver can afford and what their ceiling is both in series and in development (more on this later.)

Those who can stay in the game the longest will have access to better coaching, teams, and resources. No amount of advanced analytics, racing sabermetrics, or other indicators can override the fact that “making it” to IndyCar is becoming increasingly reliant on who can provide more money to teams. Many of the findings I come across in my research are tied to funding. A 2022 Marshall Pruett article estimated that 10ish IndyCar seats at the time were based on the driver providing funding to the team, and while I lack knowledge of the financial situations of IndyCar teams, I can assume that number is way more likely to have risen than fallen.

Across the USF Pro Championships, nearly every season of every level has a gap of around 30-40% in average finish between the highest performing team and the lowest performing team. While a lot of this can be determined by driver quality, the lack of elasticity in which teams are at the top (generally Pabst Racing, Velocity Racing Development, and Exclusive Autosport, who have won eight of the last twelve driver’s championships and seven of the last twelve team’s championships) show that it is fair to assume at least some of this variability can be explained by the strength of the teams.

This leaves a significant gap in how we look at motorsports prospects, and as more IndyCar teams like Chip Ganasssi Racing and Ed Carpenter Racing begin to establish partnerships with lower level teams to enhance development pathways, a question continued to play in my head:

Is there a better way to look at young open-wheel drivers in America, one which levels the playing field, if even slightly for opportunity?

This is a very imperfect science and my background is as a journalist, not in data analytics. But, as someone more immersed in the USF Pro Championships paddock than most, seeing drivers rise from USF Juniors or USF2000 to become Indy NXT or IndyCar competitors, I really wanted to give this a shot. After a few weeks of dedicated research and compiling nearly 4,000 data points from race results over the past four years, I’m going to share an (albeit imperfect) metric I created that might be able to answer my above question to some extent, and use existing data to draw conclusions that could be of benefit to academies and parents making decisions for their young drivers.

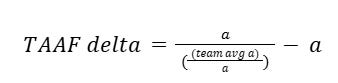

I’d like to first introduce everyone to my metric, Team-Adjusted Average Finish. It’s calculated by dividing a driver’s average finish over the races they compete in over the average finish of every driver on the team individually, divided back by their own average finish. I then subtract the TAAF from the average finish of the driver to find the difference between the team-adjusted metric and average finish, giving me a stat I will call TAAF delta.

The one major limitation is that for single-car teams, you can’t track performance relative to teammates. They’ll show up in the data as having a TAAF delta of 0.00, but given how few USF Pro Championships drivers run in one-car teams, I don’t expect this to impact the data too much.

Drivers who have a positive TAAF delta perform negatively compared to their teammates, as their average finish is worse than the team’s.

Drivers who have a negative TAAF delta perform positively compared to their teammates, as they have a better average finish than their teammates.

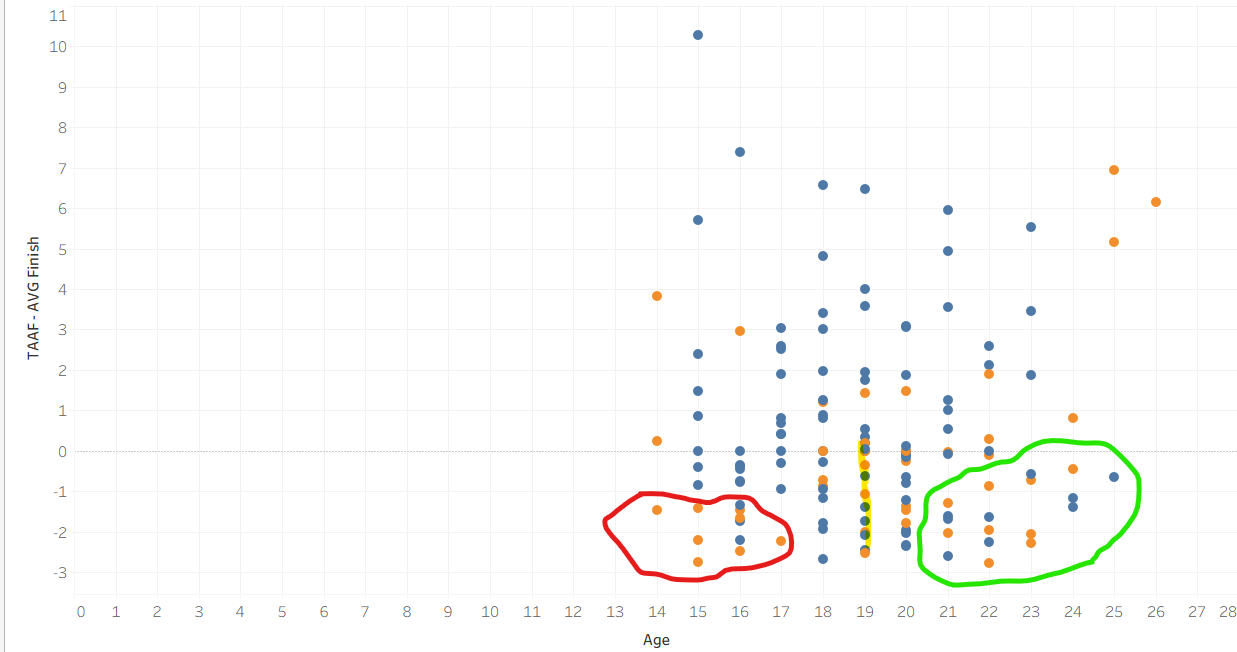

Here is TAAF delta plotted against average finish, with the drivers in the bottom left scoring favorably in both metrics. To help draw this point out, drivers who advanced to at least Indy NXT are in orange.

As you can see, drivers who advance to the higher levels of open-wheel motorsport typically have negative TAAF deltas and good average finishes. Additionally, there are very few drivers who have average finishes below 6.00 (usually what puts you in contention for a championship) who have TAAF deltas above 0.

And in case you’re wondering about the dot with the average finish of almost 2 separated from the pack, that is not a current IndyCar driver, that is Max Garcia this year with Pabst Racing. Garcia will be a common outlier through this report, and these metrics will show off just how statistically dominant he is. There’s no great comparisons to him in this dataset in nearly any metric, but I plan on extending this back to 2015 to get comparisons between him, O’Ward, Herta, and Kirkwood.

TAAF delta’s strengths don’t lie with drivers as talented as Garcia anyways, who would outperform their teammates in nearly any scenario and win championships at any USF level. It lies in looking at some of the blue dots. Guys who haven’t had the opportunities to progress to the next level but consistently outperformed their teammates.

By the time I’ve looked at this data, I refined my earlier research question and broke it up into two. One that refined what I was looking for beyond just good prospects who could break into IndyCar someday.

What kind of results and growth trajectories do top American open-wheel prospects (Max Garcia, Alessandro de Tullio, Myles Rowe, and Nikita Johnson) have that set them apart from the rest?

And then take that to answer:

Are there any drivers currently in the USF system who may warrant a closer look from teams at the next level based on their performances, either those could be on similar trajectories or those passed up on due to a lack of opportunities with top rides?

I’m going to present a few findings in an attempt to answer those two questions. Then, I’m going to list off some hidden gem drivers at the USF2000/USF Juniors level that have high levels of potential on paper. I’ll follow that up by listing limitations of this research, and ideas on what the next steps would be to enhance these findings and bring more valuable to scouting teams and parents looking to make decisions for their young drivers.

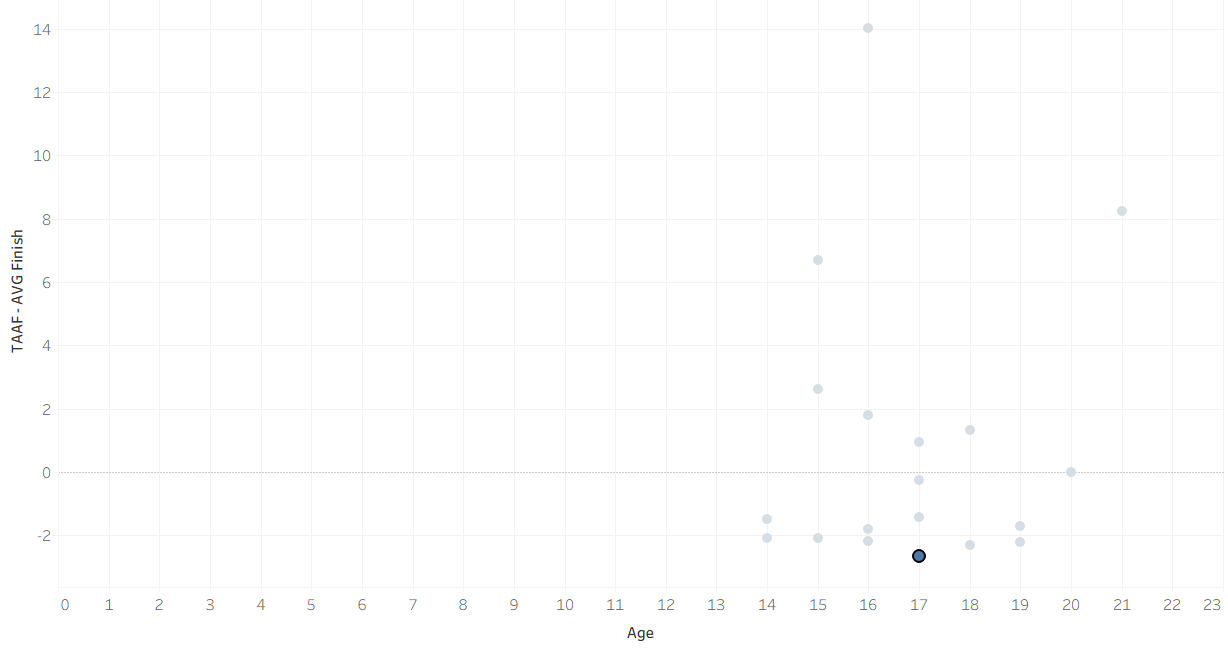

A quick look at this graph plotting age versus TAAF delta for USF Pro 2000 and USF2000 drivers lends credence to the idea that while having great seasons at that level is important, the key to quick advancement might be to take your chances at USF2000 at a younger age if ready.

Max Garcia and Max Taylor had the two of some of the best USF2000 seasons compared to their teammates in recent history in 2024. They both land in our red circle, where themselves and other dominant peers in their age who have put up similar numbers have reached the next level.

They both took early jumps into USF2000, Garcia in his age 14 season and Taylor into his age 16 year, right after his later start into car racing. And in their first seasons, they struggled significantly compared to teammates. See the two orange 14 and 16 year old dots at the very top of the chart?

Those are Taylor and Garcia’s rookie seasons in USF2000.

It was a huge jump for both drivers and the only season either of them had a positive TAAF delta at any point in their junior careers. It’s why we shouldn’t count out drivers after one year, and instead look at their year-to-year growth.

Garcia and Taylor’s TAAF delta in 2024 improved by five points each, more than any other driver in the field. Despite signs in 2023 that jumping early to USF2000 might have put them behind the ball on development, the early jump paid off in the gained experience. Once again, more money to run two seasons, and both were on top teams. Every single driver who has run two consecutive years in USF2000 and USF Pro 2000 did considerably better than their teammates in year two.

And in part due to their massive improvement, they got rewarded with moving to Indy NXT for 2026 with ABEL Motorsports (via scholarship for Garcia) and Andretti Global.

Additionally, both drivers who have advanced to IndyCar from USF Pro Championships in the past few years, Nolan Siegel and Louis Foster also had negative delta seasons in 2022 at the ages of 18 and 19 in the range highlighted in yellow.

However they find themselves in a cluster surrounded by many drivers who have fanned out. Again, funding plays a big role in Siegel’s case and Foster was supported by the championship-winning scholarship. So, ironically, our two IndyCar drivers have come from the age cohort which has produced the least Indy NXT drivers.

The reasons why a lack of 18-20 year olds have jumped up to Indy NXT and found success in recent years is because those with the talent to reach NXT at 14-17 can overcome having the funding for only a few junior level seasons, while once you reach your fifth or sixth year trying to reach Indy NXT, you’ve expended upwards of three million dollars.

Even drivers who are in the green circle, another cluster of NXT drivers (de Alba, Rowe, Hughes), often had to take breaks, try other disciplines, or step away from racing entirely for years at a time to preserve funding. I’d like to call this stoppage drivers typically reach around 19-20 the Brick Wall of Funding. I will get back to it.

Also on this chart we find some of our young, blue dots which may point toward drivers who may be underrated.

The two drivers who are looking really promising and who are in the middle of Max Garcia, Nikita Johnson, and Max Taylor are DEForce Racing’s Sebastian Garzon (top), who finished 8th in USF2000, and Teddy Musella (blue) of Velocity Racing Development, who finished second in the USF2000 championship. Both had the best TAAF delta amongst USF2000 drivers under age 18 by nearly a full point, and match the numbers of people we’ve seen have success at USF Pro 2000, Indy NXT, and IndyCar.

Garzon’s development reminds me a lot of Garcia’s, with both being prominent karters who had a transition year in USF2000 instead of heading to USF Juniors. But finishing eighth in the championship, people may not have looked too closely at Garzon in his first season. On a DEForce Racing team where the combined average finish of the drivers sat in fourteenth, his performance to pick up four top-fives signaled that in the right environment, he is lightning in a bottle to have a breakout year.

Musella is in a similar boat. Despite having a year of open-wheel experience in Ligier JFC (a regional series that runs old-generation Formula 4 cars), he had a quick development curve in 2025 where he picked up top fives in every race on the entire back half of the season after getting only four in the first half. Thanks to that streak, he was able to emerge from his teammates and comparatively perform on a level against them which would indicate potential.

Liam McNeilly (age 19) was unable to finish out the USF2000 season, but it is worth noting that his stats would have 100% drawn out the same conclusion, if not more. In order to prevent outliers, drivers who drove less than one-half of a season are excluded from a given year’s charts.

McNeilly had the lowest TAAF delta of any driver across any USF series since 2022 in 2024 when he took second place in USF Juniors with a -3.15.

While in USF2000, a TAAF delta below -1.00 can be a strong indicator of future success, early signs from the USF Juniors series across its first four years show that the number for there looks closer to be -2.00. While around 50% of the drivers with TAAF deltas below 1 in USF2000/Pro 2000 have made it to Indy NXT, only 12% of drivers with TAAF deltas below 1 in USF Juniors across its first three seasons have won a single race in USF2000 or USF Pro 2000. Once you push that to 2, it becomes 80%.

So then you can apply the same predictive measures to 2025 we used to find Garzon and Musella.

Liam Loiacono (highlighted below) is the driver that stands out by far and away the most here, with a TAAF delta of -2.65 in his rookie season of USF Juniors. While he’s at the age of 17, which is the age drivers typically begin to hit funding issues at a much higher rate, Loiacono’s season is considerably elite given his competition and equipment and all predictive measures point towards wins at the USF2000 and USF Pro 2000 level, being in an analytical group where 80% of drivers have won at the next level.

Rodrigo Gonzalez as well is a driver who at age 19 is a bit older than most of the elite drivers we see come from Juniors, but when you adjust for the performance of his teammates, he has a TAAF delta of -2.2, putting him second amongst all drivers in USF Juniors this year. He has a similar growth trajectory to Thomas Schrage, who just posted a -1.95 TAAF delta in his 20-year-old season.

So, we can begin seeing some patterns here, and some drivers like Garzon, Musella, Loiacono, and Gonzalez stand out as the leading contenders to be the next Garcia, Taylor, and de Tullio. Additionally, guys like Ariel Elkin and Vilho Aatola stand out as drivers who if given the opportunity in top equipment could win races throughout the USF Pro Championships.

On the other hand, drivers like Danny Dyszelski and Nicolas Giaffone who put up great TAAF delta numbers that would’ve gave them Indy NXT potential were sidelined and forced out of open-wheel racing due to funding issues.

Five USF Pro Championships drivers who may be hidden gems based on analytic performance, watch this space in 2026:

Sebastian Garzon

Liam Loiacono

Teddy Musella

Rodrigo Gonzalez

Vilho Aatola

The next step for this research is going to be including results from years dating back to 2015, so we can have more current IndyCar drivers in these comparisons.

Additionally, consideration will be made to the limitations of TAAF delta. Most notably, that it may underrate some drivers who are on strong teams. Alessandro de Tullio had a TAAF delta of only -0.16, making him a driver who might’ve been overshadowed by the metric by being on a 2022 USF Juniors Velocity Racing Development team that performed 40% better than the rest of the field, the most dominant team in this dataset.

I look forward to doing more analytics work, and seeing how it can help inform us about which drivers might deserve to have a good chance, and which drivers will ultimately be able to win races at the highest level.

Leave a comment